The evolution of an idea

A tale of using AI to rapidly prototype, build, and evolve a personal software tool.

Last summer, I was scrolling through my email’s sent items looking for something I had sent months ago, and saw a message I had sent to myself containing just a URL. It was Manim Community Edition, and I recall coming across it, finding it interesting, and wanting to save it in case I had a use for it in the future. The link sat in my inbox until it drifted out of sight due to the accumulation of other messages. This is unfortunately not uncommon, as I often email myself links to interesting things for lack of a better organizing system. For me, browser bookmarks are fairly useless as they lack any context - just a title and URL. These emails-to-self are not much better, except they are more visible for the brief period when they’re near the top of my inbox. After rediscovering this forgotten link, I decided to think of a better system for storing and recalling all of the miscellaneous links to interesting and/or useful things I come across.

Thinking about the problem for a bit, I came up with a few requirements:

- Low-friction: The mechanism for saving an item needed to be no more difficult than sending an email.

- Additional context: If I save a link, I want more information than just a URL and title. What does the link point to? An article I want to read? A software tool I might want to use someday? A video to watch?

- Search: I might have a vague idea later about something I saved - can I quickly find it by typing in some relevant keywords?

What follows in this post is my experience building a tool to meet these requirements. Tools do not spring into existence fully formed. Like ideas, tools are often inchoate at first, and need to be evolved and refined into something concrete.

That’s exactly what happened with this tool. It has taken on three distinct forms, each one an informed evolution of its predecessor. With all three forms, I relied heavily on AI coding assistants like ChatGPT Codex and GitHub Copilot, tools that are themselves rapidly evolving!

Iteration One: The Mac App

When thinking about “low-friction” ways of saving items, I was reminded of the macOS Screenshot app’s elegant interface for capturing a screenshot of a window: you open the Screenshot app, click Capture Selected Window in the toolbar, then simply click on the window you want to capture. That’s it! This seemed very promising to me. If I had a macOS app living in my menu bar, I could click it to activate the screenshot window selection mode, and then select the web browser window with the URL I wanted to capture. That would be very low-friction!

Now, the tool would be capturing a screenshot of the browser, not a URL. But is that really a downside? The browser screenshot will help with my second requirement: additional context. And the fact that it is a screenshot image and not text is not at all important - because we have at our disposal powerful multimodal AI models that can easily extract text from screenshots!

This became my plan for the first iteration of the tool:

- Create a macOS app with a menu bar icon and drop-down menu for capturing a screenshot of a window

- Trigger the macOS screenshot selection interface, available via Apple’s ScreenCaptureKit framework

- Send the captured screenshot to a multimodal OpenAI model and ask it to return text, such as any visible URLs and perhaps even a summary

- Display the screenshots in a list, with a details pane showing the AI analysis results

- Have a search box to perform free-text search of the AI’s text output

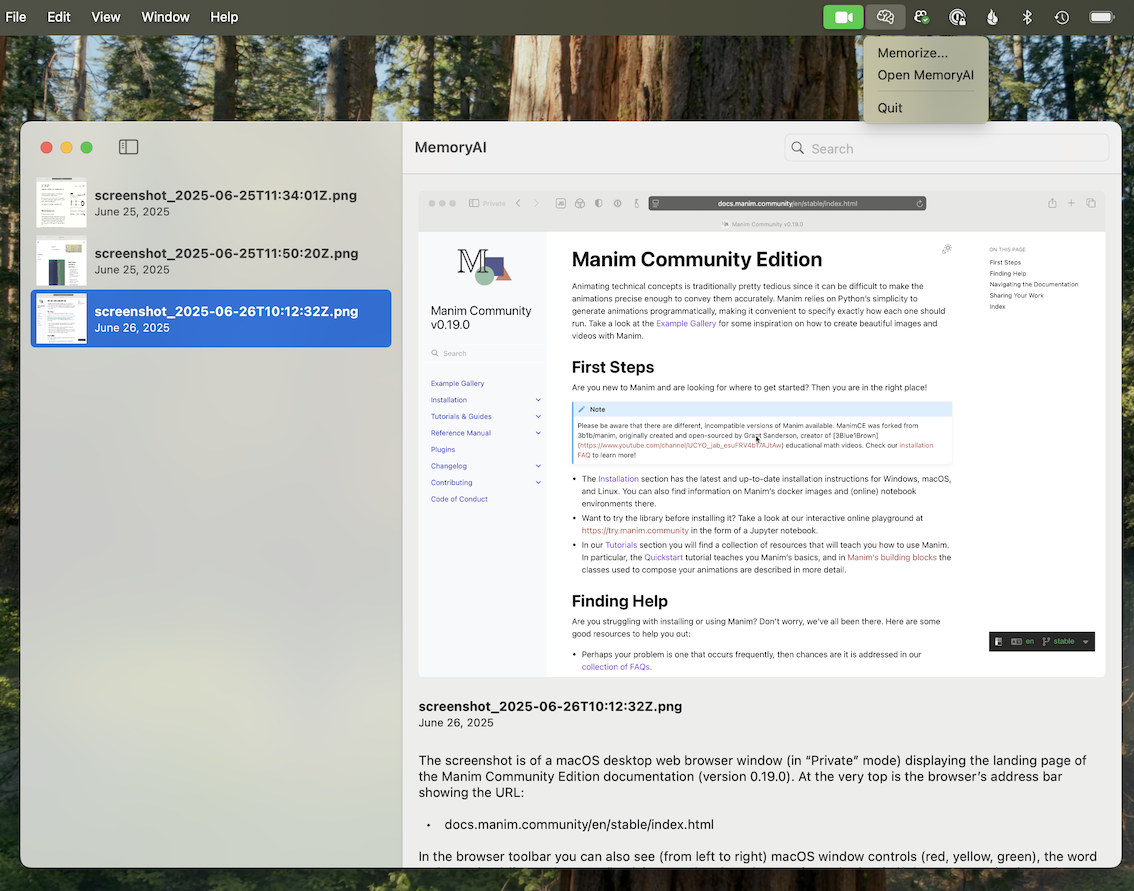

As I have limited experience programming in Swift, there was a lot of trial-and-error as well as back-and-forth with various AI coding assistants before I finally managed to get a basic version of the app working:

I could already tell from this minimal proof-of-concept that the tool would be quite useful in practice. It was very satisfying to open a link, find it interesting enough to save for later, click an icon to activate the screen capture, select the relevant browser window, and have the screenshot appear in my app! Then, a few moments later, an OpenAI model’s analysis of the screenshot would appear below it.

After using the tool for a bit, I quickly realized I would need to make the list of screenshots accessible from other devices, like a phone or iPad. I briefly considered building a companion iPhone/iPad app that could share the screenshot database via iCloud, but that struck me as quite complicated. It would also limit the devices that could access the data to those signed in to my personal Apple account. I came to the conclusion that a more straightforward solution would be to just build a web implementation and host the tool in the cloud.

Iteration Two: The Web App

I knew that the web app wouldn’t be able to completely replace the Mac app, as the quick window screenshot ability can only be partially replicated within a web app (see the Screen Capture API). The convenience of having an easily-accessible button or keyboard shortcut that activates the window capture interface was too great to give up!

So one option would be to have the Mac app’s sole purpose be to capture the screenshot and send it to the web app server, which would handle the user interface for displaying screenshots as well as the OpenAI-based image-to-text functionality.

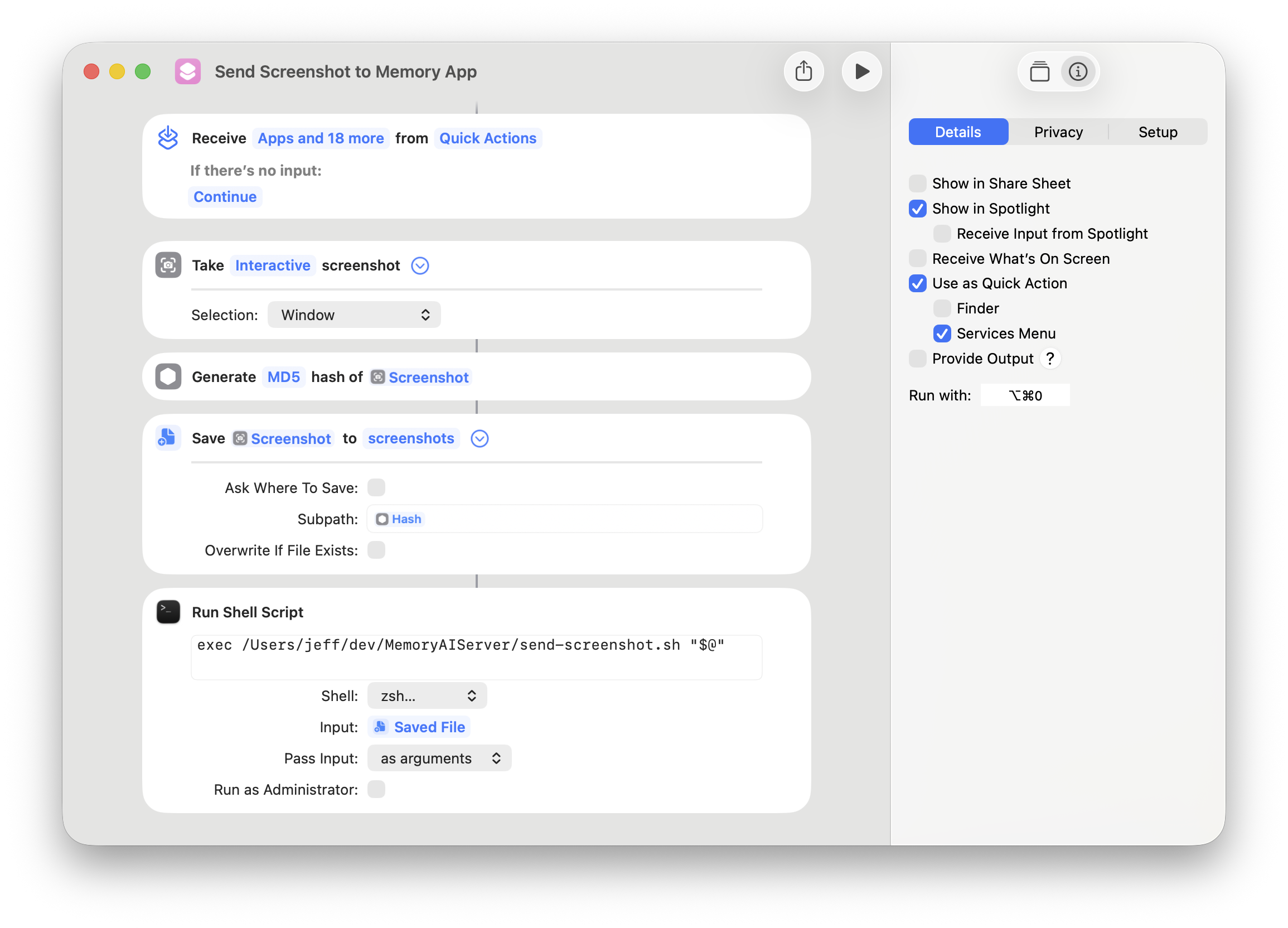

As I started working on the implementation of the web app, I stumbled upon the screenshot functionality in the Mac’s Shortcuts app. It turns out one can build a shortcut that triggers the window selection interface for taking a screenshot, and the resulting screenshot image can be used in downstream actions - including passing it to a shell command:

The Run with: option in the right pane even allows you to assign a keyboard shortcut. With this functionality, I could completely replace the Mac app and rely on this shortcut instead. All I’d need to develop is a small script that accepts the screenshot file and uploads it directly to my web app.

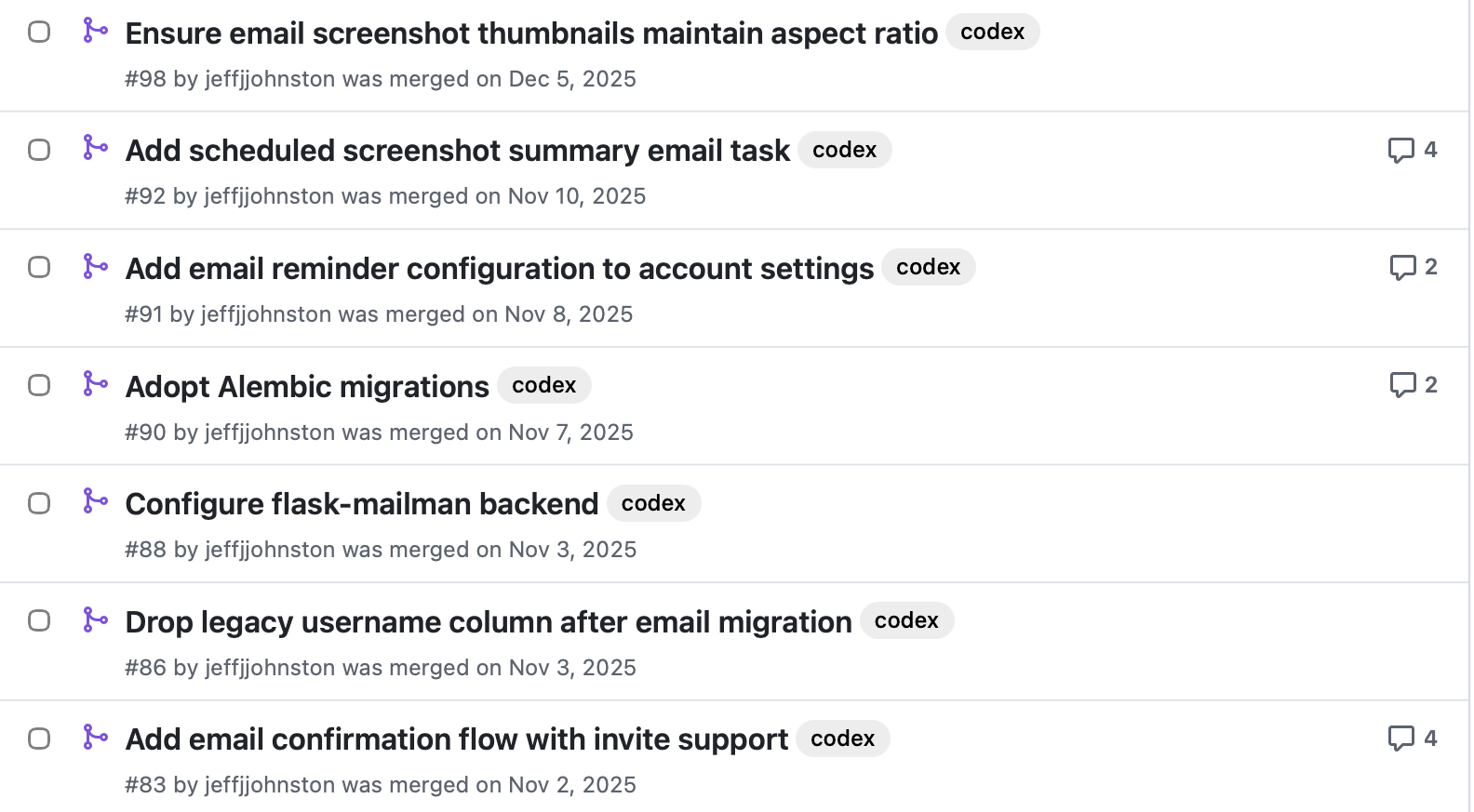

Building the web app was very educational. I relied heavily on ChatGPT Codex cloud’s asynchronous tasks, allowing me to request specific features and enhancements and then review the coding agent’s proposed changes in the form of GitHub pull requests. The agent helped me develop an automated deployment strategy for pushing new versions from GitHub to the Amazon EC2 instance hosting the app. Looking at the private repo now, there are 75 pull requests with the codex label. Here are just a few:

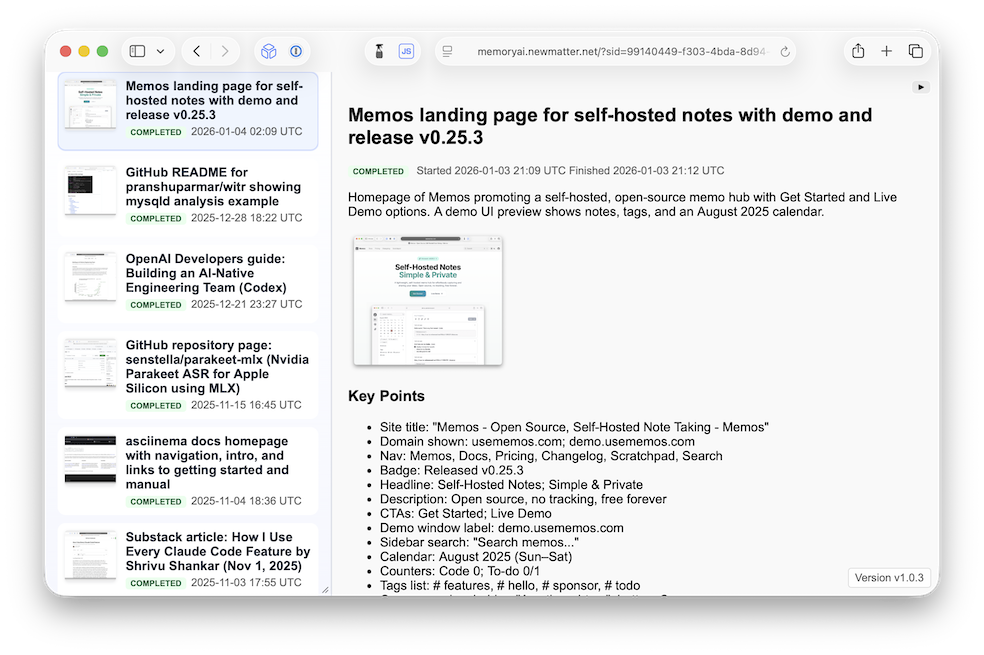

The web app gradually became more and more polished, eventually reaching a stable state:

It features:

- User accounts with email-based logins and invite-code-only registration

- Queue-based asynchronous processing of new screenshots

- Full-text search

- Manual upload of new screenshots if needed

- Server-sent events to automatically update the UI when new screenshots are added or analyzed

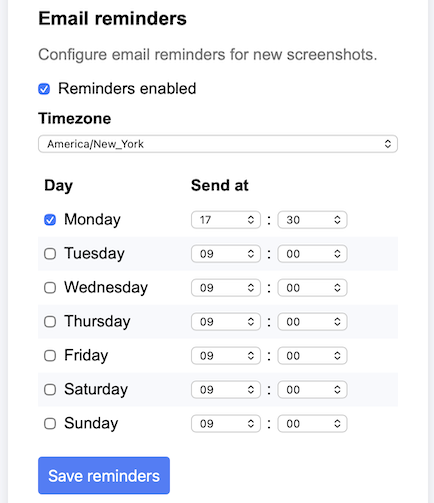

While using this iteration of the app, I decided that it would be very useful if the app could send me emails on a specific schedule reminding me of all the new screenshots I had added since the previous email. This was a complex undertaking involving significant configuration in both Amazon Web Services and Cloudflare, where my domain is hosted. The result was a simple UI and a backend scheduling and email sending system:

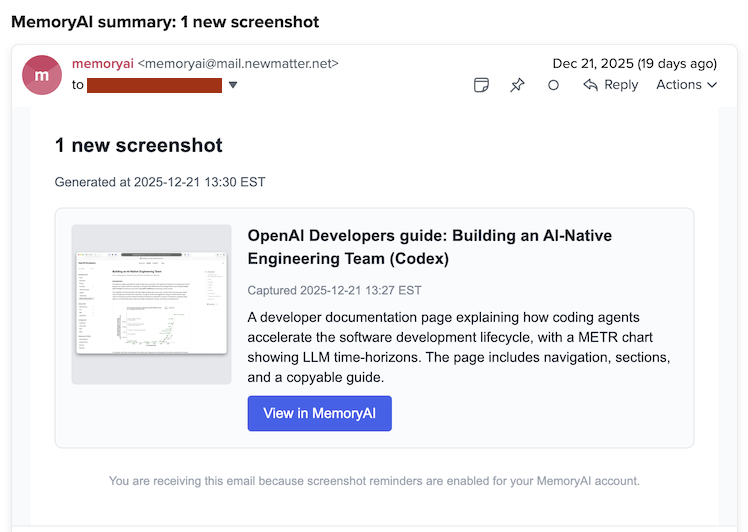

Now I can get a helpful reminder of new screenshots:

At this point, I felt that the tool met all of my original requirements and I was using it fairly regularly. But I began to see a number of limitations:

- There is no way to edit the AI model’s screenshot analysis text

- Screenshots are the only input accepted

Addressing these limitations would turn the tool into a more general-purpose notes database that could handle more than just screenshots. Adding UI code to allow for editing rich text and defining new, non-screenshot records in the database didn’t strike me as the best way forward. I eventually asked myself - does this need to be a standalone tool, or could it instead be a feature of a larger, more capable app? The critical feature is the ability to quickly capture a screenshot and use an AI model to annotate it with additional context. What sort of existing app might benefit from this feature?

Iteration Three: The Invisible Plugin

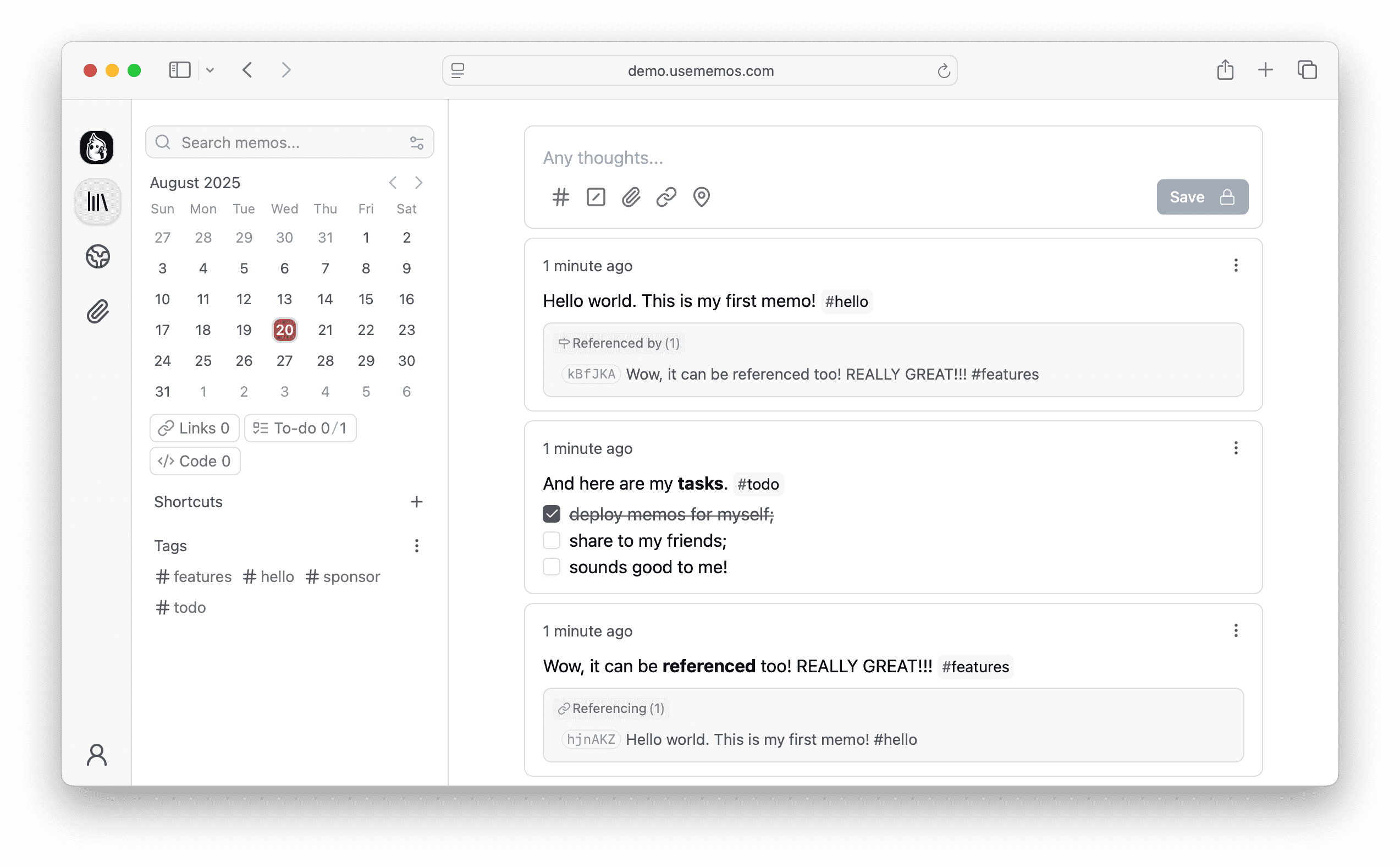

One answer to the question above might be: a general-purpose note-taking app. A great free, open-source, and self-hosted example would be Memos:

The Markdown-based notes in Memos support attachments, links, tags, code blocks, and more. Memos also has a full API for interacting with the app programmatically, as well as webhook support for event-based integrations. The next iteration of my tool was beginning to take shape in my mind:

- The Mac Shortcuts-based screenshot system could be modified to create a new note in Memos with the screenshot attached

- The Memos webhook system could notify my tool of the newly-created note with its attached screenshot

- My tool would grab the screenshot from Memos, send it to the OpenAI model, and then update the note in Memos with the resulting Markdown analysis from the AI model

- The existing email reminder system could be adjusted to query Memos for new screenshots on my desired schedule, just like the web app

Now, my tool wouldn’t really be an app at all - it would be an invisible process running behind the scenes, automatically annotating screenshots as they are added to Memos. I’d get the benefit of all of the features built-in to Memos, such as the ability to edit the AI’s screenshot annotation text and store non-screenshot notes, all while maintaining my original requirements that had driven the development of the previous iterations.

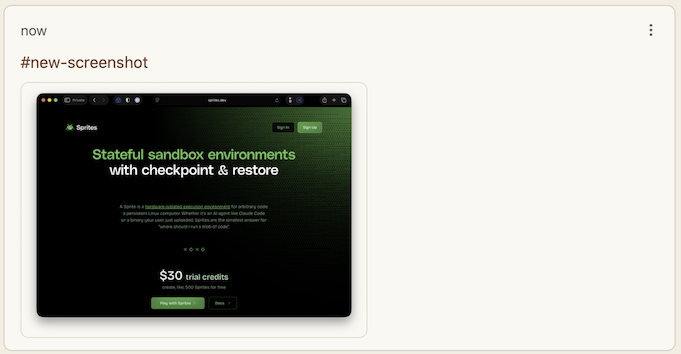

When a new note with a screenshot is added to Memos, either manually or via the Mac Shortcuts-triggered script, I ensure it gets the #new-screenshot tag:

The Memos server then sends a webhook event to my tool’s server, which processes the new screenshot and updates its contents with a Markdown-formatted version of the AI model’s annotation, replacing #new-screenshot with #screenshot to signal completion:

That’s the current implementation of my original idea. Will it evolve further? Probably! I might think of additional features I want, or find an app other than Memos to integrate with. But for now, I’m satisfied with the way it ended up, as it provides a convenient, central place for me to store interesting links and more.

Lessons and realizations

I wrote this post to show that the process of building software, especially personal tools that start out as just-barely-defined ideas, is rarely a linear path. What I find incredibly exciting about AI coding assistants is the ease with which they allow one to explore different possible paths that arise when creating software. The three iterations of this tool are a great demonstration of that. I doubt I would have attempted to implement these major evolutions of the tool without the aid of AI coding assistants and their uncanny ability to rapidly add features and rearchitect code.

I am certain we are witnessing the cusp of a sea change in the way software is built and maintained. Software is going to become more diverse and flexible, as the cost of adding custom features will drop precipitously as more and more of the work gets delegated to AI models. Software developers now have a new form of intelligence available to them, and it is already clear that this intelligence allows both individuals and teams to build things that could not have been built before.